My 2 km walk brought me along a stretch of Naas canal.

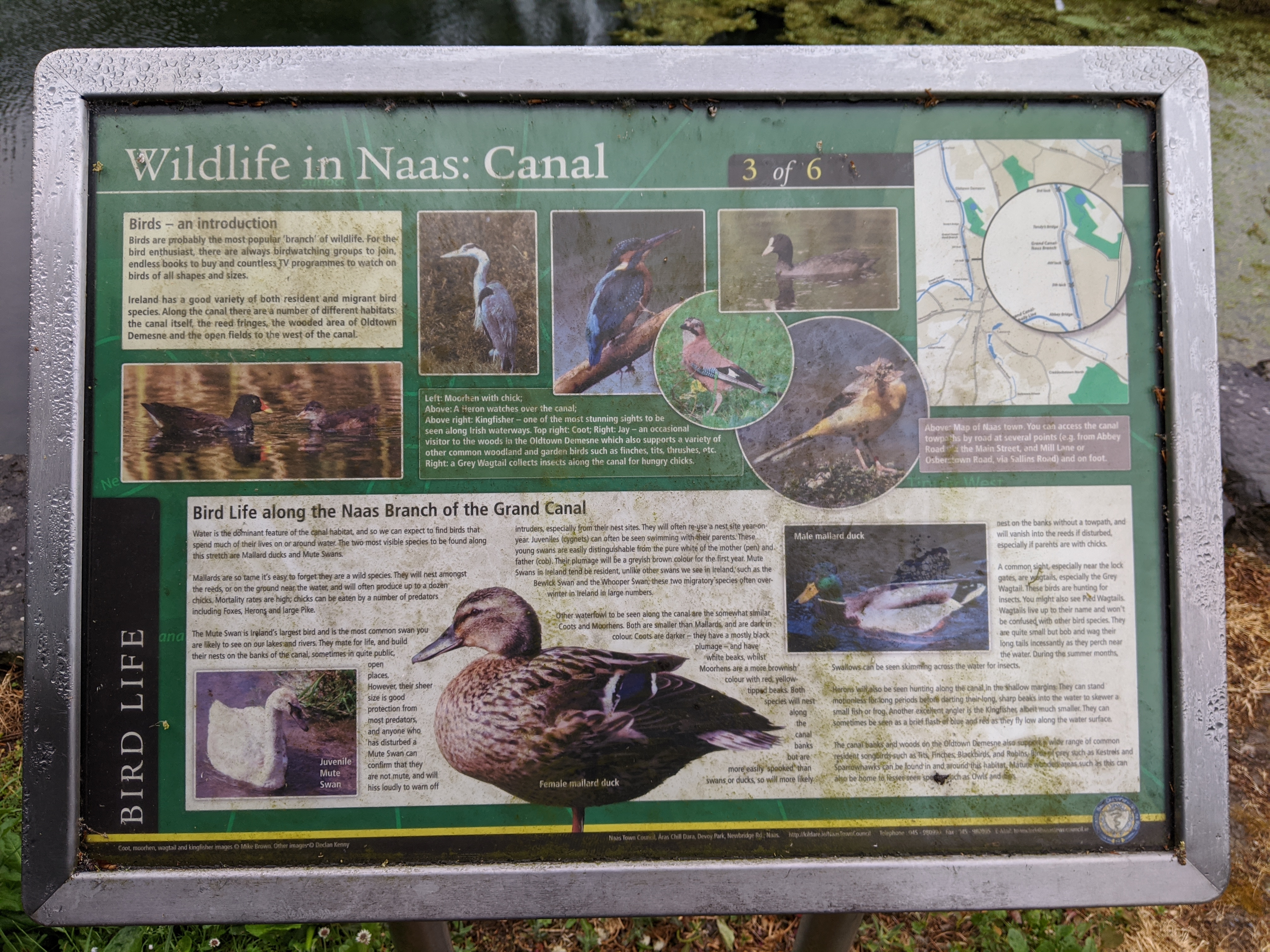

Naas Town Council has as put up ‘Historical Trail’ information points and information about the canal wildlife.

My map is in response to the information provided, as there is little mention of pre-Christian Gaelic culture. This is a ‘Mythological Map’ to draw attention to how mythology can allow us to access Gaelic culture and history even when it appears absent.

The only reference to Gaelic culture on my walk was the names of

the Children of Lir (who were turned into swans) on four trees as part of a children’s ‘Fairy Trail.’

Fairies can be read as a relic of Gaelic mythology: it has been suggested that the fairy tradition in Irish folklore refers to gods and goddesses (the Tuatha Dé Danann or the Sídhe) who were given fairy status after Christianity had become the dominant religion in Ireland.

The wildlife information points provide information about habitat and behaviour. However, there are mythological connections to animals along the canal as well such as the crow, horse, otter and eel.

Horses feature heavily in Irish myth. It is on a horse that Niamh and Oisín visit Tír na nÓg and the white waves of the sea are called the horses of Manannán, the sea god. In continental Europe, one of the main goddesses was Epona, who is often depicted riding a horse.

In the Táin (one of the most well known myths about Queen Medb and the warrior Cú Chulainn), the goddess the Mórrígan offers to help Cú Chulain but he refuses. Furious, she vows to work against him in his battle with Queen Medb's forces. In one instance as he is crossing a river she transforms into an eel and tries to trip him up.

In Irish, the name for otter is Madra Uisce- literally meaning 'water dog'. Cú Chulainn, who is associated with dogs has a geas (a curse or a magical restriction) not to harm dogs. The Mórrígan, in the guise of an old woman tricks him into eating dog meat, and as he lies sick in a river he kills an otter with his sling. At this moment, he realises that he has broken his geas and that his death is close.

Crows can be seen in tall trees all along the canal. In the Táin, the Mórrígan usually takes the form of a crow over battlefields. She is the decider of war and a goddess of death/ fate. One of her names is Badb, the Irish word for crow. Having pursued and tormented Cú Chulainn throughout his life, she lands on his shoulder in her crow form when he dies.

Another way to access Gaelic culture is through trees, which the council provides no information about. The dominant trees on the canal are beech, sycamore and chestnut, which aren’t indigenous to Ireland. There are indigenous trees as well though, such as oak, hawthown and ash.

The oak tree features heavily in Gaelic mythology. Kildare (Cill Dara) means Church of the Oak. The oak was seen as sacred to druids and is often associated with them – one Roman account of British druids says they would perform rituals near oak trees.

There are plenty of neo-pagan resources with information on the medicinal use of trees. Oak can be used as an antiseptic and anti-inflammatory for minor wounds and skin infections.

One of the information points mentions St. Patrick’s well: a site where St. Patrick is said to have baptised people. The well is on a private estate with no public access.

The Naas Historic Trail gives no information on the function of holy wells in pre-Christian Ireland. Water was usually associated with goddesses and healing. Many Irish rivers are named after goddesses, such as the Shannon and Boyne. Celtic hoards of gold offerings have been found in rivers and bodies of water.

Accounts from the 1930s schools collection (on Dúchas.ie folklore collection) tell of people visiting the well for healing and to drop coins in or to leave medals. One account says that a ring of trees surround the well, suggesting a continuation of pagan tradition within a Christian context.

Naas Historic Trail tells us that the Moat was used by the kings of Leinster, but was then built on by Vikings, Normans and finally became a British outlook point. There is a private residence on top of the moat now and it is inaccessible.

Simon Tuite from Monumental Ireland gave me some information about the Moat's connection to mythology. It is thought that it is the burial place of a goddess called Nás, who was the wife of one of the major Celtic gods, Lugh. The historic trail tells us that according to Bardic tradition, the moat was founded by someone called Lewy of the Long Hand. This may be a connection to Lugh, who is often referred to as Lugh Lámhfada (Lugh of the Long Hand/ Arm.)

This information contradicts the accepted translation of Nás na Ríogh, which we were told meant Meeting Place of the Kings. Simon Tuite told me that there is no Irish word ‘nás’ meaning meeting place. Instead he points to the Dindseanchas, a text from the 10th century manuscripts which claims Naas was named after the goddess. The first accounts of the name were actually Dún Nás (Fort of Nás), Nás Laigheann (Nás of Leinster) or An Nás – Nás na Ríogh came later and more likely just means Naas of the Kings to reference the kings who lived there in the past. None of this information is given by the Naas Historic Trail.

Simon Tuite also told me that he has contacted the National Monument Service, who suspect that the Moat may be a passage tomb, but no excavation has been carried out.